Liberating Symbols Publishing (LSP) is a non-profit centre in Switzerland, responsible for the publication of the works of Medhananda and of Yvonne Artaud, as well as their translation from the original English into other languages.

What are the books about?

Just as their teacher Sri Aurobindo explored the profound psychological self-knowledge veiled in the symbolic language of the Rishis (the seers of the Vedic era of ancient India), Medhananda and his long-time collaborator Yvonne Artaud investigated whether such knowledge could also be found in ancient Egypt. They discovered that ancient Egyptian images likewise contain a wealth of psychological self-knowledge, as do the myths, fairy tales, and parables of other ancient cultures. The seers and sages of those times conveyed their experiences through symbolic images. The language of the soul is a language of images.

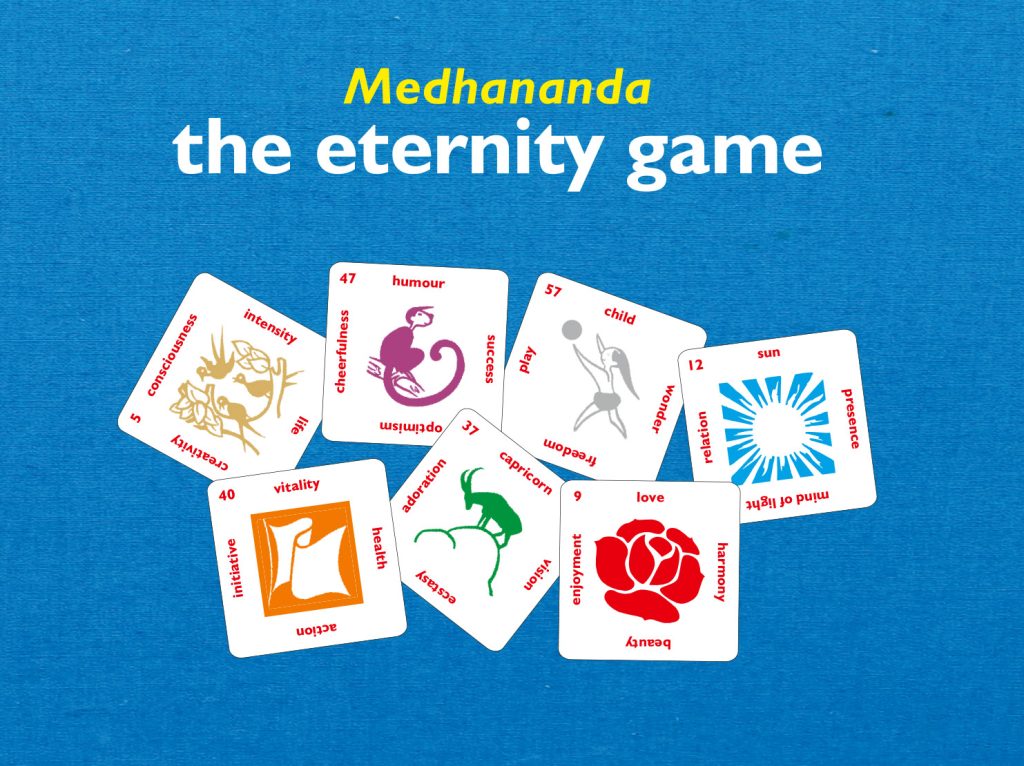

In his books, Medhananda presents numerous such symbols, and his comments help us to see their deeper meaning: Behind the many strange gods and curious figures he perceives aspects of ourselves, soul forces, archetypes as well as universal principles, within the myths and ancient narratives he recognises processes of inner development and possibilities of our being.

It becomes clear that what we call our ‘I’ (our person) is not a singularity, but that many forces act within us, belonging to different levels of consciousness and therefore often in conflict with each other. Becoming aware of our multiplicity is the first step towards transforming our small ego-formation into a greater, integral self. This is the authors’ aim.

Adults today primarily function on the mental-rational level of consciousness, characterised by logical thinking and grammatically differentiated language, and mainly focused on the material world. Medhananda shows in his books that in earlier times, a different level of consciousness predominated: it was focused on the inner world, the soul; dreams, spirituel experiences, mystical revelations, the unfolding of soul forces were more important to the sages and seers than the material world. ‘Seeing’, not philosophical ‘thinking’, was central.

We can learn a lot today from the psychological self-awareness of these ancient ‘seers’, if we approach and consider ancient documents from a psychological viewpoint – rather than from a historical, mythological, artistical or religious perspective – asking ourselves: “What can this image, this monument, this parable still show me about myself ?” Medhananda invites us to such identification exercises, that help us to grow beyond our apparent limitations.

This level of consciousness, once fully unfolded in former times, still constitutes us (among others), and is especially active in pre-school children. Medhananda, and Yvonne Artaud, emphasise that in education, alongside today’s predominantly verbal communication, symbolic communication should also be fostered: The combination of both leads to greater plasticity, harmony, and integral human growth.

The topics of the books in brief

Medhananda’s books unite or integrate areas such as:

- Psychology as well as ancient Egypt (and other ancient cultures)

- Human consciousness as well as spirituality

- Personal growth as well as ancient wisdom.

They are addressed to all who are interested in these subjects, wish to know themselves better, and want to work consciously on their own development.

Further information you will find on www.medhananda.com.

The major works of Medhananda and Y. Artaud

are the five books on ancient Egyptian symbols. They contain numerous images (drawings of Egyptian originals in black and white) that are perceived as expressions for soul powers, as movements of self-awareness, inner experiences. The authors comment their insights in a delightful, clear, well understandable way and in a poetic style, with many cross references to other cultures, sages, ancient myths and tales.

While there are many books on Egyptian mythology, religion, art, and philosophy, there are hardly any that deal with the psychology and self-awareness of the ancient Egyptians.

For those who are looking for more information about the books

From a letter from the authors: “…We attempt to let them [the Egyptian images, the symbols] express themselves in their own symbolic way, as psychological ‘koans,’ as messengers of an ancient gnosis that addresses our depth, height, and breadth, as well as our wholeness (wherein lies their healing power), rather than our intellectual intelligence.

Therefore, our interpretation had to be based directly on the symbols and the movements of self-awareness they express, and not exclusively on the so-called ‘interpretatio graeca,’ which all too often replaced the content of the Egyptian image with terms of Greek philosophy and mythology. We are immersed in a still novel paleography and are thrilled by our discoveries…”

In the preface to ‘The Way of Horus’ we read:

Isis – the empty seat, Atum – the sleigh, Re – the circle, Hathor – the House of Horus – have much to teach us, not as objects or geometric figures, but as ideograms, as teaching images, as representations of mental processes, movements of consciousness. Symbols in general, and hieroglyphs in particular, differ greatly in their function from verbal communication. Words separate things and emphasize their differences; but symbols show what they have in common. This is the reason why the translation of symbols into words does not convey their innermost meaning, and for the same reason, the study of symbols cannot be an analytical science.

In this respect, our own research differs from the general trend of an Egyptology that has not yet broken away from the so-called ‘interpretatio graeca’. Scholarly Egyptian dictionaries, with their rich harvest of phonetic translations, will certainly continue to be an indispensable tool for research. However, we believe that the conventional, purely grammatical-philological study of hieroglyphs largely ignores the psychological content of ancient Egyptian images. Hieroglyphs and Egyptian teaching images were the expression of a holistic worldview. Therefore, they can only be approached with a holistic approach that asks the right question: “Who am I, and what is my relationship to the whole?”

In the preface to ‘Archetypes of Liberation’ we read:

The purpose of this book (and the Egyptian imagery within it) is to make us aware of our greater self and its eternal principles, to see them as parts of ourselves, as threads in the tapestry that we are. What is called, in different cultural contexts, our true self, our self, or our soul—that which remains when we pass from one life to another—is not a simple, single entity.

It is like a vast ‘molecule’ built around a nucleus, composed of many psychological aspects or archetypes, each in its own invisible way connecting the One with the many, involution with evolution, timelessness with time.

What was called ‘Neteru’ in Egypt—and later in religions ‘angels’ or ‘gods’, imagined outside of oneself—are possibilities, qualities, and abilities that man must discover and develop if he truly wants to be himself and live at peace with himself. Sleep and death, our soul-vessel, our vibrant serpentine nature, our capacity to blossom, our vast emptiness, our fullness—all these are psychological archetypes, modes of being and processes of transformation, teachers of liberation, forces of self-creation. What seemed to be outside and above man reveals itself within us as a very personal possibility of being, consciousness, and bliss that we can aspire to and realize. As Sri Aurobindo says, “What seemed so far above us is here within us.”

In the preface to ‘The Pyramids and the Sphinx’ we read:

There is a simplistic view of history in which man is supposed to have become continuously more intelligent, more wise, as time progressed from age to age. And also as one looks back in time, man is deemed more ignorant and savage.

Thus it is at first difficult to accept the facts presented here because they imply that the ancient Egyptians knew more about psychology than we do today.